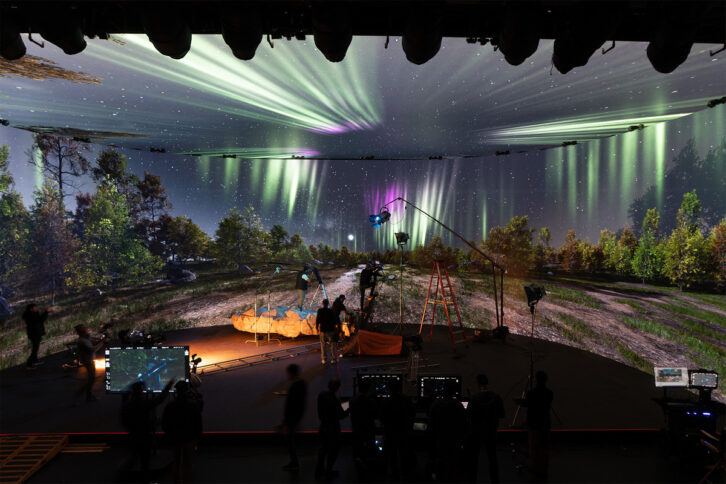

The relatively sudden arrival of a huge new industry in the form of virtual production (VP) cannot be denied. Enabling film and TV producers to shoot against real-time virtual interactive backgrounds in studio environments, VP began to mature around the same time as the Covid lockdowns arrived and made location or large-ensemble shooting highly problematic and often impossible. No wonder, then, that an unprecedented flurry of new VP studio spaces and solutions have hit the market since the early months of 2020.

Although not all of the dedicated studio environments have survived – in particular, there has lately been a more cost-conscious trend towards the use of temporary or multi-purpose spaces – VP is still growing rapidly. According to Grand View Research, the global VP market size was valued at USD 2.10 billion last year and is predicted to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 18.2% from 2023 to 2030.

Inevitably, applications in film and TV production continue to drive the sector, with many media companies also clocking that it can be an invaluable tool in decarbonising their operations. But there are also increasing signs that VP technologies and techniques are being applied to other sectors, including corporate and – in particular – education.

DISTINCT STRANDS

For vendors, systems integrators (SIs) and the purposes of this article, VP in education can be split into two distinct strands. The first concerns the development of VP-specific degrees and other training in an increasing number of universities, aimed primarily at enabling the technology’s evolution in film/TV by providing the necessary, highly-skilled talent.

The second focuses on the use of VP to support immersive and collaborative learning in other areas of education, especially those involving multiple disciplines like art and fashion. A VP facility currently being installed at the University of the Arts London – outlined later on in this article – gives a good indication of what is now possible. Both strands will be explored here.

As Sony Europe’s senior trade & segment marketing manager Adam Dover told Installation in late 2023, ultimately pre-empting the focus of this overview: “In the education world, I think virtual production is a massive thing at the moment. We’re seeing a lot of universities making significant investments in VP technologies, [which means] LED walls, camera technologies, and so on.”

For many colleges and universities, many VP courses are being introduced as additions or extensions to existing creative technology qualifications. This is the case at the University of Portsmouth (UoP), which this autumn is due to receive its first intake for a new Virtual Production BSc (Hons) degree that will give students access to specialist equipment from the University’s School of Creative Technologies. The course will hone both technical and creative skills, providing an opportunity for “creating high-quality content for LED screens behind the actors, virtual mapping using VR and game technology, and capturing performances for characters and fantasy creatures using motion capture.”

COURSE CREDITS

Senior lecturer Niki Wakefield brings to the course a wealth of experience as a screenwriter and freelance compositor, whose credits in the latter capacity include Children of Men and the first four Harry Potter films. Having won a government grant some years ago, the UoP already had a “really big motion capture studio” and other facilities that made VP a logical addition: “I teach on computer animation special effects and we kept hearing about virtual production,” she says. “It was a really big buzzword going around, so we wanted to establish this [new course] and give students the chance to get really involved with it.”

Modules in the first few years focused on coding for Unreal Engine – the 3D creation tool that underpins many VP projects – as well as modelling, VP research and practical studio experience are followed in the third and final year by major independent and group creative projects. “We’ve essentially done a crossover with modules from film, games, computer animation and effects, and added bespoke virtual production modules that bring all of this technology together,” explains Wakefield. It’s an approach that also ensures students are “not just stuck in game engines all the time” – they will also be learning about physical filmmaking.

But whilst Wakefield’s enthusiasm for the new degree is palpable, she confirms that it hasn’t necessarily been easy to connect with potential students – an inevitable byproduct, perhaps, of a technology that has evolved much more rapidly than the public discourse around it. “The industry is obviously buzzing about [VP], but it can be difficult for college and school kids to really know what it is. So part of the duty of the university is to give college students the chance to come in and visit the studio [on open days] so they can get super-excited about it and realise that it is a potential career for them.”

More generally, it’s probable that the scope of VP training and research as a whole will be improved by greater collaboration between academic institutions. A prime example here is the UK’s XR Network+ Virtual Production in the Digital Economy initiative, which is funded by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council and intends to establish “a ten-year research agenda for VP-related content and consumption for the creative and digital economies.”

COLLEGE COLLABORATION

Led by the University of York and providing funding and support to researchers working in VP technologies, the scheme is being conducted in collaboration with other institutions including the University of Edinburgh and Cardiff University.

This kind of collaboration is likely to become even more critical as media technologies and disciplines evolve and intermesh – sometimes in unpredictable and/or highly intricate ways. Indeed, Wakefield indicates that getting a foothold in the high-tech areas of the industry is harder now that access to the main software tools is “so democratised and anyone can start making anything now”, which means that students do have to be much better, from the early stages of their career, “in order to secure the jobs”.

Simultaneously, VP-related education is also being provided from other quarters – including the vendor community. Hence, therefore, the training Academy set up by Mo-Sys Engineering, which is a leading manufacturer of VP solutions, camera tracking, image robotics and remote production.

Explaining the initial inspiration for the Academy, Mo-Sys CEO Michael Geissler says that the company wanted to give people the opportunity to understand and learn VP. “It’s quite a responsibility to turn up to a shoot and, as the DP [director of photography], everybody’s looking to you to perform with [VP], which is still a relatively new technology,” he says.

“So a big priority for the academy is to give people the space to become confident with the technology, which we achieve by having small groups of no more than three or four people around one camera system – meaning that they are really able to get muscle memory.”

In addition to its own academy – which operates in London, Los Angeles and Bangkok, and offers 3-day, 5-day and full Foundation courses – Mo-Sys is working closely with universities as demand for VP education increases. “We have a strong focus on education now,” confirms Geissler, who suggests that the VP trend is now at a point where it is becoming a significant criteria for some students in choosing where they want to study.

Meanwhile, a project exemplifying the potential of VP for education beyond its application in the film and TV worlds is represented by an installation taking place this spring at the aforementioned University of the Arts London (UAL). The University has signed the first deal to install Sony’s Crystal LED VERONA Displays as part of a new virtual production stage at its London College of Fashion Campus at East Bank. Delivered via UAL’s Fashion Textiles and Technology Institute, the new VP initiative aims “to create capacity for innovative, trans-disciplinary practice-led research in VP/XR textiles and dress.”

UAL worked with display technology specialist Lux Machina to test all major brands, ultimately concluding that the Sony solution was best suited to delivering “both deep black image expression and low-reflection performance that greatly reduces the contrast loss caused by light from adjacent LED panels and studio lighting equipment.”

The University will also utilise Sony’s Virtual Production Tool Set – a software-based solution that allows users to design the picture they need for VP for creative projects – while researchers will be able to pre-visualise scenes and creative concepts using Virtual VENICE for Unreal Engine to develop, pre-visualise and configure the Crystal LED displays for rapid deployment of VP projects.

Surveying the development of VP as a whole, Jee Hee Lee – Sony’s European product manager, Crystal LED – highlights the likelihood of further simplification and benefits for the creative industries as technologies evolve.

In terms of education, she says Sony will continue to be engaged in “broadening the understanding of its virtual production solutions, which hold significant potential in educational settings”. These solutions enable the blending of physical and digital elements to create immersive environments, offering “numerous opportunities” for collaborative creativity.

Echoing the sentiment of Wakefield’s remark, Lee alludes to the scope of VP as a wider creative tool that can help to bring together different educational disciplines. “Students can develop skills in many areas by working in the virtual world. So yes, there is a lot of potential to deliver this expertise to the education market,” she says.

SPECIALIST ENVIRONMENT

It’s an observation to which CJP Broadcast Service Solutions – a Herefordshire, UK-based company SI and solutions provider specialising in VP environments for cinema, broadcast, education, corporate and sports – can also attest. The growth of the sector as a whole, suggests sales & marketing director Kieran Phillips, is due in no small part to the fact that the technology has “finally caught up”.

“Affordable processors can now provide enough power, and of course the Unreal engine delivers very good quality, photorealistic graphics in real-time,” he says. “Large LED screens and volumes, aligned with precision camera-tracking, mean you can shoot very complex scenes live.”

Consequently, the constraint now is not the technology, but the creative and technical staff to make it happen on a wider scale. “Universities have rapidly responded to this crisis, and we will see the situation easing in the near-future,” he adds. “[But] whilst the talent has caught up, we are still far off from seeing the talent demands being met.”

CJP is certainly doing its part to address this shortfall by working extensively on projects in colleges and universities. Education, confirms Phillips, is “very much” a specialist field for CJP. “The future depends upon a rapidly growing number of young people entering the media industry who have a real understanding of modern production methods and can hit the ground running with a new creativity,” he says.

“We have built facilities – including virtual production studios for broadcast, film and games – for a number of UK universities, including University of Sunderland, the University of the Creative Arts and Southampton Solent University.” Just announced at the time of writing was the development of a new VP suite for Basingstoke College of Technology.

Echoing a view voiced widely during interviews for this article, Phillips perceives great potential for VP in a myriad of creative disciplines. “These university facilities prepare media students for careers by giving them access to the tools they will be using in the professional world. But their influence is bigger than that: they introduce other disciplines to new forms of creativity which can have a transformative effect on their specialist fields.”

He goes on to quote Professor Arabella Plouviez of the University of Sunderland, who remarked: “What really interests me is the opportunity to involve students from across the faculty: writers, musicians, performers. It can involve animators or fashion students; it may bring in colleagues in business law or tourism. The potential is here for a whole lot of students to work together and create.”

UPSKILLING TALENT

CJP is also mindful of the need to “upskill existing talent” – a recognition that has involved the construction of its own XR Studio: “This means we can now introduce any person from any background to the latest operational and technical workflows involved with virtual production,” says Phillips. “[In addition], providing training to existing professionals in the industry will allow for the longer development of new talent coming through from further education and higher education.”

Meanwhile, the company is continuing to work closely with leading developers in virtual studio technology – such as Mo-Sys for camera tracking and graphics generation, Xsens and Faceware for motion capture, and Aoto for LED volumes – and is “constantly reviewing what technology is coming to market”. Like many others, Phillips is also of the opinion that VP will be employed in a variety of other contexts and points to a recent initiative with StartUp Croydon to develop the Creative Digital Lab in South London, which is a complete VP environment available to anyone in the business and charity sector.

As he points out: “The core benefit of virtual production – the ability to conjure up a complete environment which may be too fantastical to realise or too expensive to shoot in – at the click of a mouse in a controlled space is applicable in so many fields.”

TELEVISUAL FEEL

Leyard Europe – whose video walls and floors scale to any size and offer small pixel pitches that allow for high-resolution images – is another vendor to have recognised the opportunities heralded by new learning practices. “When we look into education, the main driving factor for using VP technology is the rise of hybrid learning,” says VP product Cris Tanghe. “But in order to keep the students interested the content needs to be compelling. You want to break the monotony of an hour spent watching the same wide-angle shot of the professor; [therefore] VP set-ups are used to give it a more television feel.”

As Tanghe acknowledges, however, “to run such a set-up there is a lot of know-how needed”. LED walls form part of a complete solution that should be easy to operate and encompass “content creation, rendering engines, tracking, camera, recording, LED volume, etc”.

LOOKING AHEAD

Looking ahead, Tanghe is also enthusiastic about the rise of “tier 2 studios” – which include capacity for “broader use outside the movie industry” – and would welcome more standardisation around VP-related technologies, although he knows it won’t be easy. “With VP there is a lot of confusion out there in the market. You have XR/VR/AR/MR, all different sub-domains of the VP market, and [in addition] each use case is different. Setting standards is always helpful to create a guide for the community, but as it is so broad in terms of use cases, I believe it’s going to be very tricky to get one set that fits all.”

It’s also a challenge given that VP is continuing to evolve as a technical art-form. George Murphy, creative director of visual effects and animation studio DNEG, highlights VP’s scope for “pre-visualisation” in a wide variety of applications, ranging from commercials and music videos to full-length films and environments in the corporate and educational worlds.

VP also resonates with the trend for more variable working patterns: “One of the great strengths is that you can have team members collaborate together even if they’re in remote locations,” says Murphy. “Having the flexibility to work in that way can be very beneficial.”

Nonetheless, with VP increasingly approaching a point of maturity, it’s likely that more standard practices and technical standardisation – not least around the metadata involved in capture and image processing – will begin to emerge. In the meantime, there is every sign that VP will go on expanding its reach into other areas, of which education is set to be one of the most dynamic.