The growth trajectory of virtual production (VP) over the last 3 years has been nothing short of phenomenal. Given the ideal circumstances to develop during the distanced Covid era, VP has rapidly become a major sector for vendors and service providers. Hundreds of dedicated VP facilities have been built, while its techniques are being applied across TV, film and corporate work – with AV tech front and centre.

Some recent data from Grand View Research confirms that VP will continue to expand at a rapid rate for a long time yet. According to the report, the global VP market size was valued at $1.82 billion in 2022 and is expected to expand at a compound annual growth rate of 18.2% from 2023 to 2030. Among specific contributory factors, the “increased adoption of LED video wall technology” is augmenting VP across media & entertainment sectors, while VP techniques are reducing the need for expensive location shoots. Looking ahead, it is expected that AI and ML will further enhance its efficiency and quality.

But while the foundations of this sector look impressively solid, there are some issues that need to be addressed if VP’s ‘next phase’ is to proceed smoothly. Standardisation is one primary area of concern; as new technologies emerge a core process of standardisation tends to occur to make adoption smoother, and ideally VP should be no exception. Meanwhile, training & recruitment also places highly in any list of concerns as job descriptions are still being defined at a time when there is huge demand for skilled personnel.

In this article we’ll address some of the next steps to be negotiated as the VP sector matures into its next major phase.

CONSISTENT BASELINE

To an extent, the fact that VP currently revolves around a couple of 3D gaming platforms – notably Unreal Engine and Unity – has at least delivered a consistent baseline to VP production. But with so many variables in play in each project, the question inevitably arises as to what kind of standardisation – both formal and informal – is required to ensure the technology is available to the broadest possible end-user base, and that interoperability can be established between different solutions.

Intriguingly, it appears that the view is decidedly mixed across both vendors and solution providers. While some highlight specific areas (notably around metadata) that are ripe for standardisation, others imply that the evolution of VP itself will ultimately bring about the necessary simplification and accessibility.

Intriguingly, it appears that the view is decidedly mixed across both vendors and solution providers. While some highlight specific areas (notably around metadata) that are ripe for standardisation, others imply that the evolution of VP itself will ultimately bring about the necessary simplification and accessibility.

Seemingly in the latter camp is Callum Buckley, technical consultant at CVP, a video solutions provider that has made “significant investment” in VP recently. “Over the past four years, we have witnessed significant improvements across the board in virtual production technologies,” he says. “LED and processor technology has seen substantial advancements and evolved feature sets, resulting in reduced artefacts and creative limitations when shooting against LED walls. Real-time graphics performance has been drastically improved with notable additions like Nanite and Lumen to Unreal Engine. Closed hardware systems such as disguise offer enhanced reliability and solve time-consuming lens calibration or cluster rendering.

“These ongoing innovations are making virtual production technologies more accessible to a wider user base, not only enhancing overall reliability but also simplifying operation, requiring less operator knowledge and skill. As these advancements continue, virtual production technology will become the new norm in the industry, rather than a luxury.”

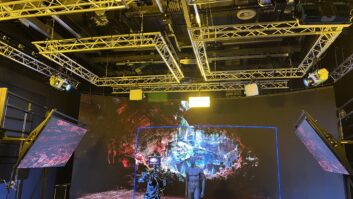

Advanced AV technology specialist Anna Valley has made a huge impression on VP during the past few years, most recently opening a new ‘black box’ studio facility in London to cater to virtual production, virtual events, and film and TV shoots. Rather than there being too many options, Christina Nowak – Anna Valley’s director of client relations, film and TV – suggests that there might not be enough options at the present time.

“While it may seem like there are lots of virtual production platforms or engines, there are actually only one or two different options for each category or function,” she says. “Emerging platforms are still in development so the market leaders don’t have a lot of competition. If anything, this is a hindrance to growth.”

Nowak’s Anna Valley colleague, project director film and TV Ian Jones, indicates that the arrival of more standard hardware will be beneficial.

“Over the next few years, we should see more hardware capable of running a variety of software applications, which will make it easier to invest in virtual production,” he says. “For example, when Unreal servers are used in conjunction with Pixera licences you can take care of both rendering and plate playback from either solution, rather than requiring dedicated hardware for each function – which helps cut down on the costs involved in virtual production.”

In terms of standardisation efforts, there are some notable initiatives underway at present, especially around metadata for various workflow stages. For instance, Nowak points to the Rapid Solutions Initiative launched by SMPTE (Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers) in 2021. Created to find solutions for on-set VP (OSVP), the group has already produced a host of educational initiatives and a camera/lens metadata report.

The initiative’s latest announcement, from April 2023, alludes to progress on multiple fronts: “The initial metadata release targets the use of traditional VFX as a step toward future releases that will cover camera and lens metadata for on-set virtual production and camera-tracking metadata. The work is hosted in a public repository where SMPTE members and the public can provide comments and feedback. Reference code is also provided that converts the output of camera makers tools into a normalised JSON format.”

The initiative’s latest announcement, from April 2023, alludes to progress on multiple fronts: “The initial metadata release targets the use of traditional VFX as a step toward future releases that will cover camera and lens metadata for on-set virtual production and camera-tracking metadata. The work is hosted in a public repository where SMPTE members and the public can provide comments and feedback. Reference code is also provided that converts the output of camera makers tools into a normalised JSON format.”

Will Newman – business development & DMPC manager, pan-European imaging products & solutions at Sony Europe – agrees that metadata ingest (the process of importing content into a server for editing or processing) is a prime area for standardisation in VP. “There are plenty of competing camera manufacturers, and we all have different ways of ingesting metadata, so I do think you will see some standardisation there,” he says, adding that the 3D engine “ideally knows everything about the camera [when ingest takes place], including positional data, information about which colour workflows the camera is using, and so on.”

NARROW DEFINITIONS

As much as the efforts of SMPTE and others are to be welcomed, there is also a widely-held view that – by its very nature – there are probably going to be more limitations around developing VP’s standard practices than in some other notable areas of production.

“While standards are important for the industry, we need to ensure that we don’t set these against a narrow definition of VP,” says Jones. “By definition, VP simply means that part of what you’re shooting isn’t physically there – whether that involves an LED backdrop or projection, camera tracking or static setups, UHD content or lower res material as a soft-focus backdrop depends on the specific project and what you’re trying to achieve. There’s a danger of setting standards to such a high level that it prices VP out of most budgets, and we need to ensure that we cover the full spectrum of content.”

Some of these thoughts are echoed by Jonathan Dyson, European LED industry development director virtual production at LED display solutions provider Absen, although he perhaps goes further than some in his reservations about standardisation.

“Whether or not formal technology and workflow standards develop for virtual production is a complex one,” he admits. “There are both potential benefits and drawbacks on either side to consider. However, it is likely that some form of standardisation will emerge in the coming years, especially as the industry continues to grow and mature. Personally, I wouldn’t want to see too much ‘standardisation’. In the creative industries, like any other art-form, you use the tools that work best for you to help you realise your vision; therefore any standardisation would surely be a prison for a creative.”

EDUCATION CHALLENGES

If different organisations place different emphases on the importance of standardisation, then by contrast there is an almost total consensus on the need to boost education around VP as the technology hits its stride. Progress is definitely being made – not least by Final Pixel Academy and several other prominent VP training specialists – but it seems there is still much to be done, not least in recruitment.

“It has been said that if training recruiters understood how to recruit the right people, that would be beneficial,” says Dyson. “The good news is we are seeing a good few universities that already run media and film courses starting to buy into this technology, and students are looking for the courses that have already structured VP into their programmes. Also, there are a number of great training companies out there, such as Final Pixel Academy and Screen Skills, who are providing day and week courses.”

“It has been said that if training recruiters understood how to recruit the right people, that would be beneficial,” says Dyson. “The good news is we are seeing a good few universities that already run media and film courses starting to buy into this technology, and students are looking for the courses that have already structured VP into their programmes. Also, there are a number of great training companies out there, such as Final Pixel Academy and Screen Skills, who are providing day and week courses.”

This is good news, because as Newman observes, there are likely to be serious financial outlays for colleges and universities wanting to offer VP training. “If you think about all the processing power, lights, cameras and so on, then it’s clear that teaching VP courses involves quite a major investment, and that’s one reason why it’s less prevalent at present. But that is beginning to change.”

There are also plenty of vendor-led developments focused on educating people to work in VR. For example, VP solutions provider Pixotope recently announced a new app, Pixotope Pocket, as part of its Pixotope Education Programme. Geared towards aspiring VP professionals, the app provides access to augmented reality and virtual studio tools and workflows.

Of course, one of the big challenges in developing and delivering VP education is that the entire area of technology is still evolving so rapidly. As Jones notes: “There is a danger that, by the time the content for long courses is written and then students pass through the course, much of the content will be out of date. It is a challenge for educational establishments and students to keep up to date with the technology, [so] it is imperative that we continue to up-skill people through a series of short courses and on-site experience. The pool of additional talent needed for many virtual production roles already exists in different sectors; professionals from the events, gaming, FX and even interior design industries have transferable skills. We just need to invest in their virtual production training.”

As daunting as the challenges here may seem, the truth is that they’re hardly without precedent in the long history of the global creative industries. Notes Newman: “If you look at the evolution of the film industry, there has been a tendency for roles to change; new ones are created at the same time as others are taken away. And that goes back to [the advent of] technicolour!”

Meanwhile, innovation by individual vendors and service providers shows no signs of letting up. For example, in April, Sony announced a Virtual Production Tool Set to help improve pre-production and on-set workflows. Designed to work with the Sony VENICE camera, Crystal LED and other HDR-enabled LED walls, the Tool Set includes a Camera and Display Plugin for Unreal Engine that allows productions to identify and solve common VP workflow issues; and Color Calibrator, a new application for Windows 10 to ensure proper colour reproduction when shooting LED walls with the VENICE camera.

New facilities also continue to open: for instance, in addition to Anna Valley’s aforementioned new studio facilities, CVP has recently established a dedicated virtual production division and will soon launch a new showroom in London.

Buckley reveals: “Our upcoming flagship showroom at Great Titchfield Street, which is scheduled to open in September 2023, will feature a specialised LED wall set-up, allowing our customers unparalleled access to virtual production technology and expertise.”

Meanwhile, as the ecosystem around VP begins to mature, it’s likely that we will also see a further evolution of mindset – one in which all remnants of the initial hype have been stripped away and people are able to focus on the creative possibilities of VP across film, TV and corporate applications.

Dyson says: “I personally believe we have passed the peak of the hype, and passed the low points and disillusionment, and we are heading back up to a much more stable and understood tool within a production on the other side.”

COMMERCIAL MODELS

We can also expect the commercial models for VP to keep evolving. After an initial flurry of permanent large-scale VP environments, temporary and more flexible set-ups are on the rise. Jones says: “As people’s experience with VP increases, and through even more thorough pre-production, the cost-effective solution for many will be to move away from permanent, fixed solution studios – and so we will see an increase in temporary or rental volumes as a bespoke setup for each production. This will mean productions only need to pay for what they need and will have complete flexibility over their setups.”

It won’t come as a surprise to read that AI is expected to have a significant impact on VP over the next few years. Ben Davenport, VP global marketing at Pixotope, remarks: “With the rise of AI, [VP] is becoming vastly more accessible and by incorporating it we can expand on what we mean by virtual production. Everything we see today – AI themed text models and image processing – will have a huge impact on the future development of this industry. Disney heavily invested in spatial computing and will want content that works on that platform; there is only one way to produce that, and that is with VP. We are already using AI in our products through tracking and image processing, and we are doing things that there was no way to do before, but now suddenly there is – and the tech is moving fast.”

It won’t come as a surprise to read that AI is expected to have a significant impact on VP over the next few years. Ben Davenport, VP global marketing at Pixotope, remarks: “With the rise of AI, [VP] is becoming vastly more accessible and by incorporating it we can expand on what we mean by virtual production. Everything we see today – AI themed text models and image processing – will have a huge impact on the future development of this industry. Disney heavily invested in spatial computing and will want content that works on that platform; there is only one way to produce that, and that is with VP. We are already using AI in our products through tracking and image processing, and we are doing things that there was no way to do before, but now suddenly there is – and the tech is moving fast.”

More than anything, however, it’s now abundantly apparent that VP is never going to be a sector in which a ‘one size fits all’ approach is remotely relevant. Hence companies across the board will have to remain highly responsive if they are to remain successful in this space.

“What’s clear is that there is no standard virtual production project,” confirms Nowak. “Every production is so unique, which doesn’t make it easy for people coming into VP for the first time. But people are beginning to realise that VP is a tool – rather than a trend or a whole production element.”