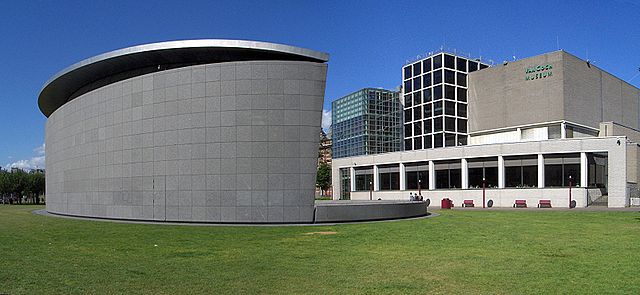

The Museumplein institution that bears Vincent van Gogh’s name – and a substantial proportion of his artistic output – has always been fittingly dynamic. But when the Gerrit Rietveld-designed building reopens this May following a period of remodelling – during which a capsule selection of its colourful treasures was presented at the Hermitage Amsterdam – there are still a few surprises in store.

While ostensibly shuttered to align the building, which turns 40 this year, with contemporary fire regulations, the museum’s curators didn’t waste the opportunity to do a little spring-cleaning themselves, painting nearly 11,000sqm of the gallery’s walls – but not the colour you’d expect. Joining the ranks of elite art institutions that have foregone white in favour of warmer hues – London’s National Gallery, Paris’s Musée d’Orsay – for the jubilee exhibition Van Gogh at Work, the gallery walls will become an extension of the canvases they display: stormy grey, vibrant cerulean and a pale blue that mirrors the walls of the artist’s bedroom in Arles. Splashes of chrome yellow are reserved for exceptional highlights – of which there are many, including original sketchbooks and the artist’s only surviving palette, on loan from the d’Orsay.

“Van Gogh’s works look good against colour,” says Nienke Bakker, the museum’s curator of exhibitions since 2010. “Plus the new décor adds to the unity of the collection.” As well as celebrating the museum’s reopening and the 160th anniversary of the artist’s birth, Van Gogh at Work, which contains some 200 pieces by the artist and his contemporaries, is also the culmination of nine years of intensive research into the painter’s technique and development. And while the museum’s new décor seems characteristic of Van Gogh’s palette, this research suggests that may not be the case.

“The colours have faded – the reds especially,” confirms Bakker. “Originally, the colours in ‘The Bedroom’ would have been quite different. During our research we found that Van Gogh had used a cheap pigment and the red had faded dramatically, turning the original violet of the walls to the pale blue we see today.”

A digital reconstruction displayed alongside the painting will reveal the original hues, and the curious can do a little research of their own, examining paint samples through the powerful microscopes used by the researchers. There were more surprises: tiny sand particles found in Van Gogh’s seascapes, and vegetative matter in his pastoral scenes, indicate that he painted on location. Evocative images of the artist in a field watching that seed-scatterer, or in that garden of irises spring to mind…But the research did much more than simply place old works in a new light. ‘”To restore a work, you first need to know what it is made of,” says Bakker. “Now we’re better able to preserve Van Gogh’s incredible oeuvre.” Here’s to the next 40 years and beyond.